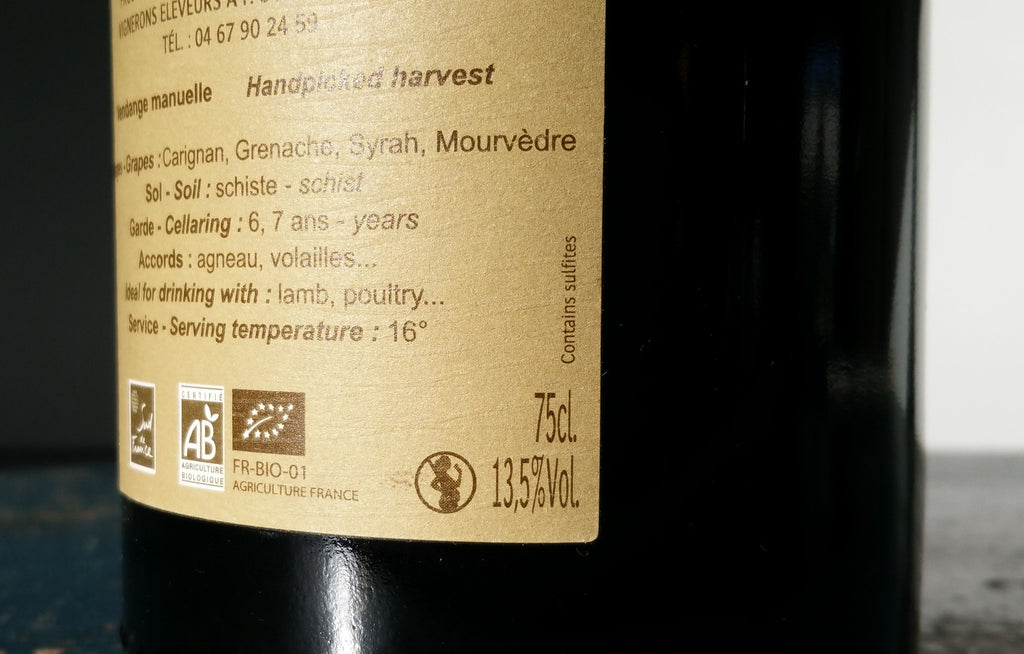

Contains Sulfites!

Almost all wines for sale in the UK have the words ‘Contains Sulfites’ on the label but is this really something to worry about?

What are they?

Sulfites are added to almost all wines to kill bacteria (which may cause spoilage) and to prevent oxidation (the wine turning to vinegar). They are a natural by-product of fermentation, so even if the winemaker doesn’t add them, there will always be a small amount in the wine.

Can I blame them for my headache?

In short, no. They're only a problem if you're allergic to them (roughly 1% of the population), but even then a headache is not one of the likely symptoms. For everyone else, the small quantities found in wine are thought to be harmless.

How do I know if I’m allergic to sulfites?

Guzzle some dried apricots and see what happens – dried fruits tend to have 5 to 10 times as many sulfites added to them.

If it’s not the sulfites then what is it?

If it’s red wine in particular that gets you, then you might have an intolerance to tannins and/or histamines. This is much more likely to be the root of the problem than the sulfites.

Alternatively it may be a result of dubious winemaking practises – too many chemicals in the vineyard for example - or some think the use of 'commercial' yeasts (bought in a bag) rather than wild yeasts (those found on the skin of the actual grape) is to blame.

With this in mind, organic and bio-dynamic wines can only be a good thing.

If they’re so harmless, why do they have to mention it on the label?

This is really a warning to the small percentage of asthma sufferers who have a severe sensitivity to sulfites.

Anything else I should know?

If the winemaker has bunged in too many sulfites then you may well detect a dodgy eggy smell.

If you are to any extent allergic to them then there are various options:

Seek out some ‘no sulfites added’ wines.

Organic and biodynamic wines have lower sulfite levels than conventional wines.

Red wine has natural anti-oxidant properties so usually has less sulfites added to it than white wine.

You can also look out for ‘natural’ wines as these are generally very low in sulfites – it is an unregulated term though so you would need to check.

Sources

The Oxford Companion to Wine

http://www.decanter.com/wine-news/eu-wines-may-now-be-labelled-organic-28964/

https://www.allergyuk.org/sulphites-and-airway-symptoms/sulphites-and-airway-symptoms

http://www.thekitchn.com/the-truth-about-sulfites-in-wine-myths-of-red-wine-headaches-100878

http://winefolly.com/tutorial/wine-headache/

http://blog.wblakegray.com/2015/02/what-causes-red-wine-headaches-new.html

Continue reading